The 3Rs of Critical Infrastructure: Responsibility, Resilience, and Reality

When a region in the Cloud goes down, it impacts people everywhere. Engineers are stressed. PagerDuty is screaming. People are asking questions. That’s not the moment to blame your Cloud provider or write cynically about single-cloud risks. It’s time to knuckle down and take responsibility.

Setting the Scene

On Monday, October 20th, 2025, a large part of the internet blipped in and out of existence. One of AWS’ busiest regions, us-east-1, went dark. A single DNS bug inside DynamoDB snowballed into hours of failures worldwide. The list of affected services was absurd: PlayStation, Snap, Disney+, Slack, Zoom. And the weird ones: VAR decisions in the Premier League and the inability to control Eight Sleep beds. It hit some harder than others, but even companies built for ultra-high availability, like Vercel and our own Cloudsmith, saw some impact.

Outages like this aren’t surprising. They range from mild and short-lived to rare and catastrophic. But they all share one thing: inevitability. Every service with real users will eventually get hit by something upstream, midstream, or downstream. The important part is not that they can happen; it's that they do. It’s that they will. It might sound macabre to suggest three certainties in life: death, taxes, and outages. But if you build services others depend on, maybe that’s not far off.

So how much should you care? As always in engineering, it depends.

Critical Infrastructure

Critical infrastructure is any system that people or businesses rely on to deliver their own value. It isn’t defined by size or marketing, but by dependency. If your outage prevents someone else from fulfilling their promises to customers, and they can’t operate, deploy, or ship because of you, you’re a critical dependency, whether you consider yourself that way or not. Your downstream might be banks, game studios, logistics companies, database providers, automotive manufacturers, trading platforms, or alert systems. Internal or external, it’s all critical.

So, it’s a big ask. But someone is paying you, so they don’t have to think about it. That’s why you exist.

The outage made me think about the “3Rs of building critical infrastructure” and why they matter:

- Responsibility: You own the story of your architecture, uptime, and blast radius.

- Resilience: Design for failure at every layer, so the system continues to run when something breaks.

- Reality: Outages are inevitable. No platform is perfect. Your honesty and preparation are what matter.

When you sit in someone else's critical path, the 3Rs are the cost of doing business well. Responsibility means you don’t blame vendors for the choices you made. Resilience means you engineer for failure as if it were a routine occurrence. Reality means you’ve got a job to do, and outages aren’t hypothetical. They’re coming. You just don’t know when.

I’ll return to the 3Rs later, explaining how we apply them inside Cloudsmith and how that might relate to you. However, it’s worth examining what happened last week, as just like backups are not real until you try to restore them, an outage of this magnitude is a significant test of the 3Rs across the industry.

When us-east-1 went down, it had a long tail recovery, and we saw a broad spectrum of responses in the industry: Some services kept operating, some degraded gracefully, some vanished (for a time). Some pointed fingers. Some used it for marketing. And some wrote about it. The best stayed calm, honest, and worked to minimize the impact.

So what did it look like for us as a vendor?

Flashback

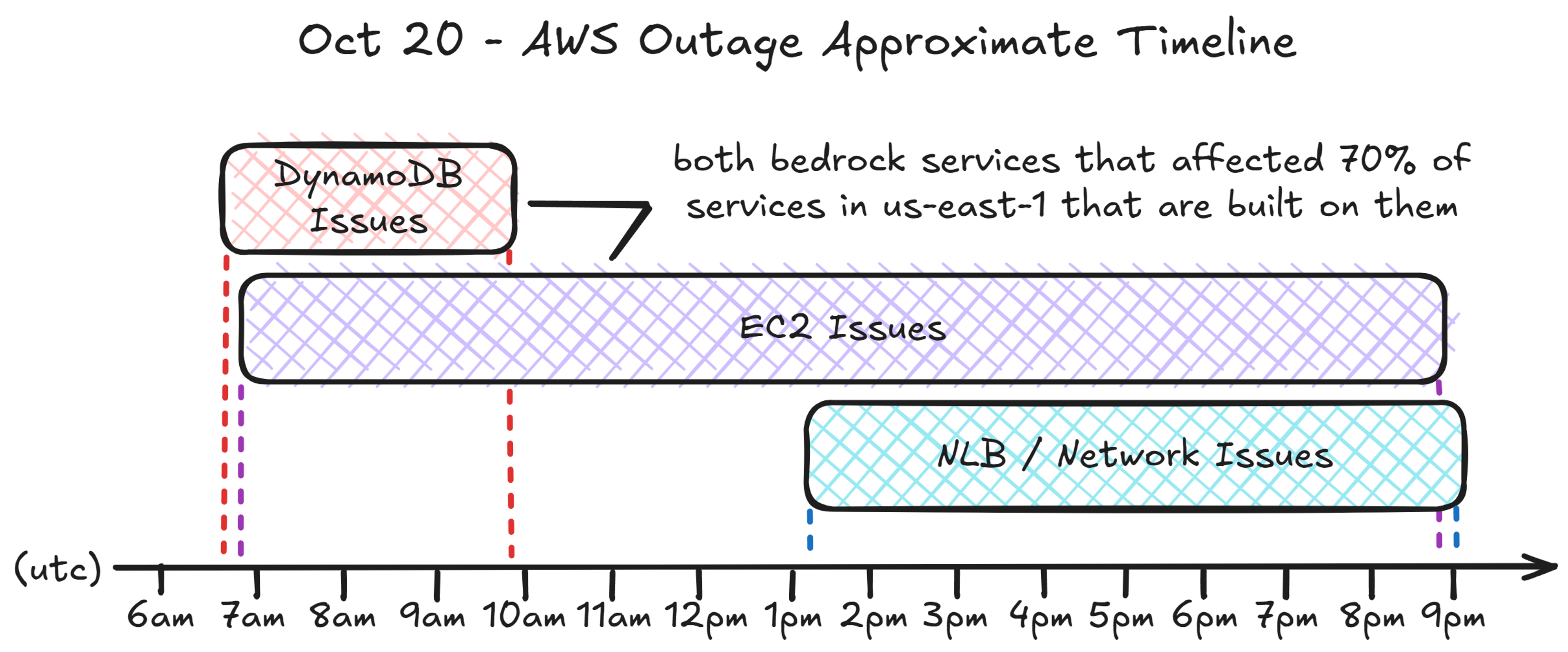

First, you don’t need another retelling of what happened during the AWS outage. If required, there’s an official post-incident review. However, I'd recommend reading one of my favorite blogs to follow, The Pragmatic Engineer, where Gergely Orosz asked, “What caused the large AWS outage?” and articulately wrote about it, with diagrams. He explains the root cause: a DNS failure in DynamoDB caused by a race condition. The failure snowballed, from the inability to start or manage EC2 instances to a thundering herd of network congestion issues. DynamoDB was down for around 3 hours, but the EC2 outage (and things built on it) extended to around 12 hours beyond that.

An approximate timeline for the entire event looks like:

Gergely also mentioned one of my all-time favorite Haikus (even though it’s not entirely the cause):

It’s not DNS.

There’s no way it’s DNS.

It was DNS.

Well, DNS, plus the bane of engineers everywhere: the Heisenbugs that manifest from race conditions. Gergely’s article also provided an excellent insider's look into how the outage was connected to other architectural components within AWS (as many people know, us-east-1 is a crucial control plane), as well as the sequencing of the events that led to, participated in, and followed the blackout. I’d also recommend “More Than DNS” by Jonathon Belotti for additional technical details. Read both and return here to continue.

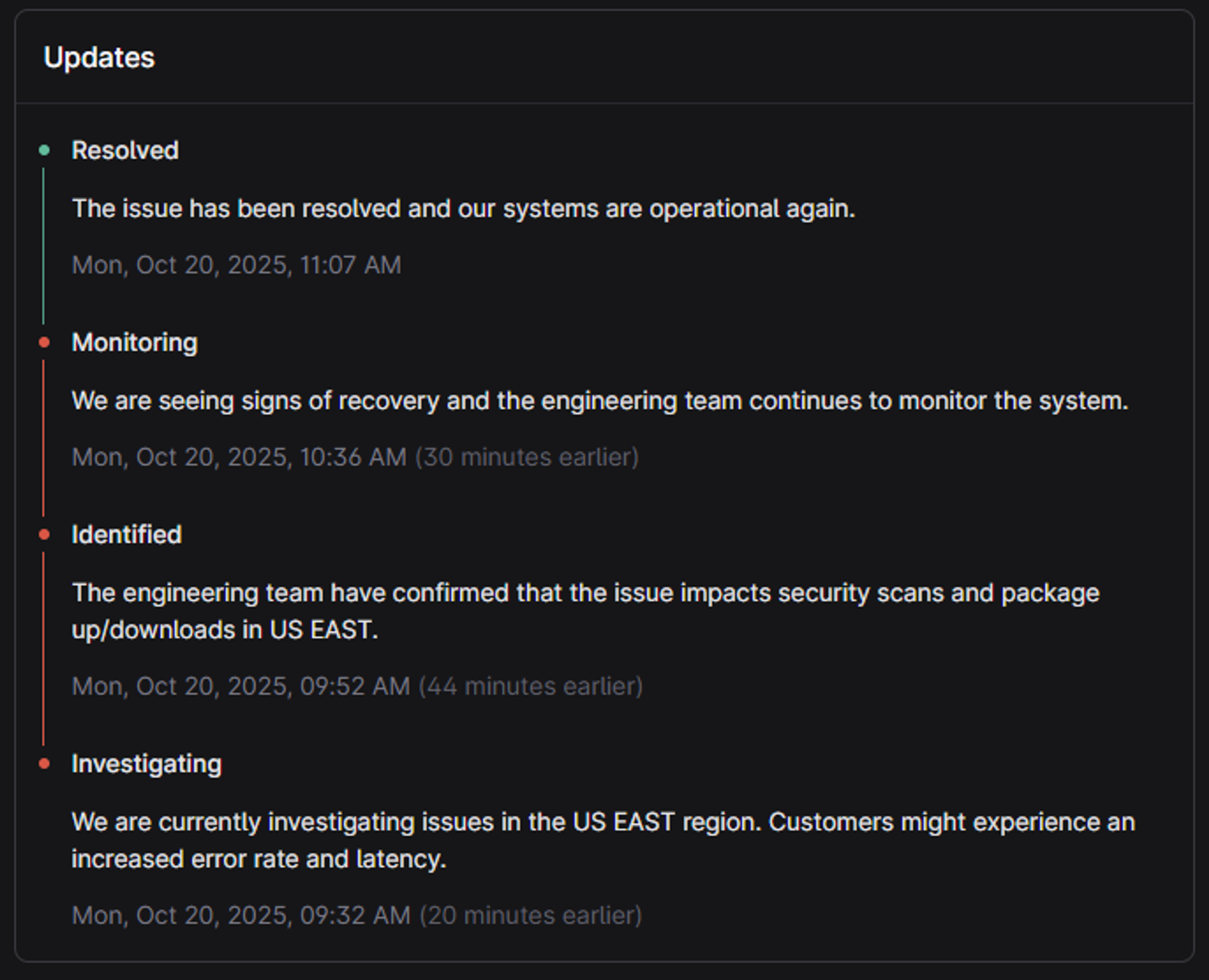

Back to the matter: What happened behind the scenes at Cloudsmith during the outage? First, let’s look at our public status page. On Monday, 20th October, we posted the following public communications (in addition to private communications sent directly). As shown, the incident from our perspective lasted for around 90 minutes:

Peering behind the veil, this is what was happening (times in UTC+1/BST/IST):

- ~9:18 AM. We were alerted to potential customer issues near us-east-1, and a low-category incident was raised as an SEV-3 (code for “may or may not be a big problem”).

- ~9:22 AM. The engineers could not start a Zoom call, indicating that the issue was possibly something more unusual than a “regular” outage. A Google Meet call was utilized as a fallback.

- ~9:30 AM. The team continues to investigate the root cause and notes that the investigation is slower due to some issues with our observability and logging tooling. However, after checking in with the team at AWS, we discovered that an incident had been raised with DNS as the potential root cause, affecting us-east-1.

- ~9:35 AM. Traffic continues to route worldwide, and most customers are not impacted; the team observes that some of our observability/notification systems are affected, requiring extra investigation effort.

- ~9:46 AM. The team notes that a dependency on pulling the latest TrivyDB from Public ECR has impacted our ability to execute some vulnerability scans and is intermittently blocking some package syncs.

- ~10:11 AM. The team notes that upstream fetching is failing for requests serviced near us-east-1.

- ~10:15 AM. The team highlights that the most significant impact is that Docker Hub is down, and a fetch bug related to tags has caused some issues for many customers. An engineer is assigned to fix it.

- ~10:20 AM. The team notes that some non-critical processes are impacted, such as slower webhook delivery broadcast in comms. In anticipation of recovery and to help with traffic routed to other regions, the team pre-emptively scales out additional resources.

- ~10:26 AM. Early signs of recovery are noted for AWS. The team notes that the Docker pull issue continues to impact customers. We communicate estimates directly with customers affected by the fix.

- ~11:04 AM. Due to AWS’ recovery and a combination of mitigations, impacted services for uploads, downloads, and webhooks are beginning to recover. Metrics are looking gradually healthier.

- ~11:07 AM. The incident is considered “resolved” due to system-wide recovery. The team notes that AWS is still encountering issues. Still, since we don’t operate critically in us-east-1, the impact on Cloudsmith and Cloudsmith customers is massively reduced at this point, enough to consider incident resolution.

- ~12:30 PM. The fix for the Docker image fetching is tested and ready for shipping, but the team is encountering issues with our deployment services. Therefore, they plan to deploy the fix manually.

Side question: You ask, how do you remember all of these details, Lee? We use Incident.io religiously to catalog everything that happens during any incident, outage, or other event. The auto-Scribe feature is a fan-favourite amongst the engineering teams at Cloudsmith. Subscribe to the church of graphs, yes, but also to the church of ... scripture? Either way, keep track of what happened.

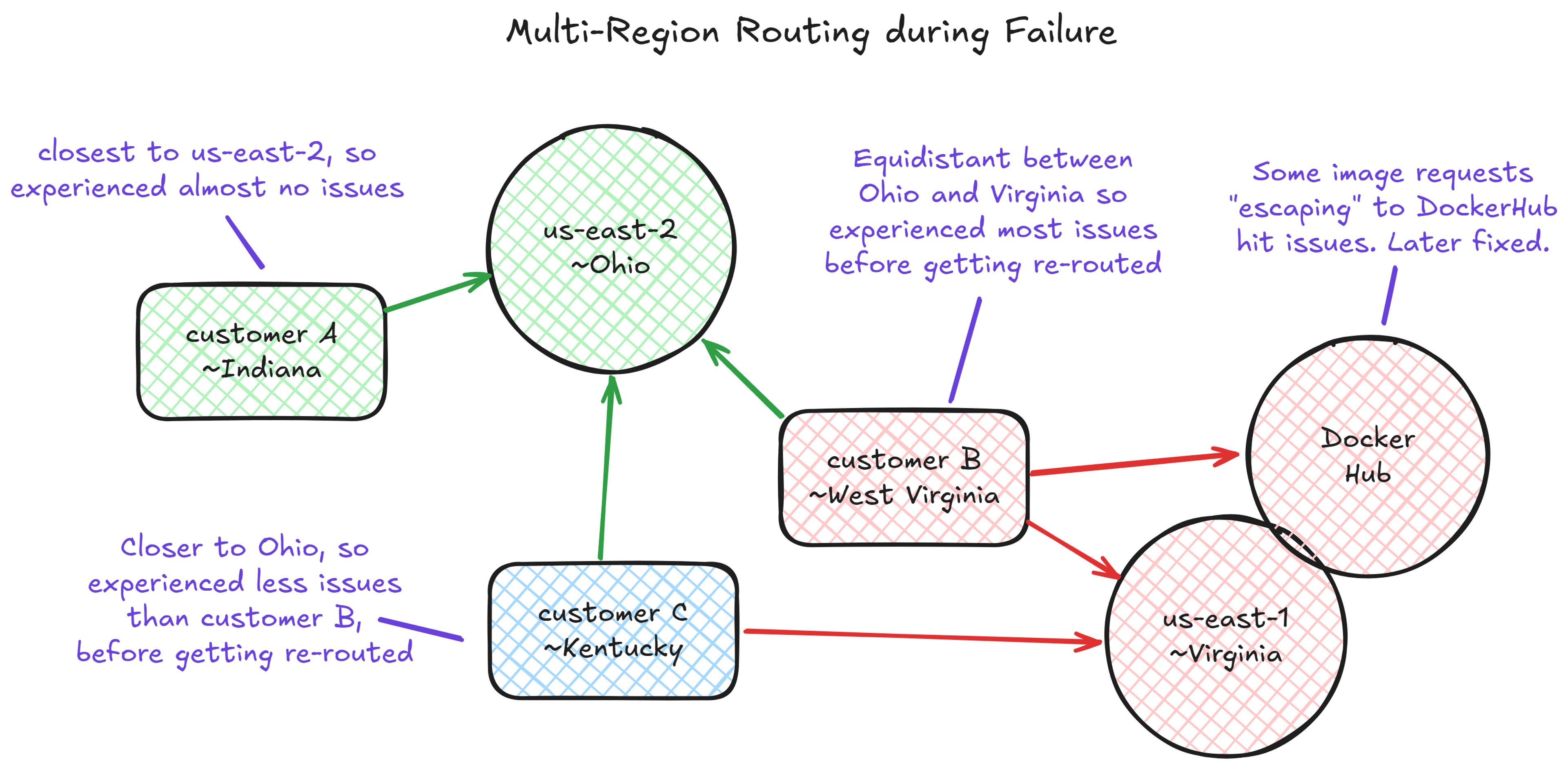

For clarity, the following provides a simplified visual of what the multi-regional routing looked like during the failure, including Docker Hub’s unfortunate downtime, which added salt to the process of pulling images for some of our customers affected by the caching bug. Aside from that, when traffic got routed away from us-east-1 and towards us-east-2, things Just Worked; this is something that often automatically happens due to latency-based routing with associated health checks (note: we run in several regions worldwide, but us-east-1 is deliberately not one of them, because we chose to avoid AWS’s control plane on purpose; we have edge nodes there, though):

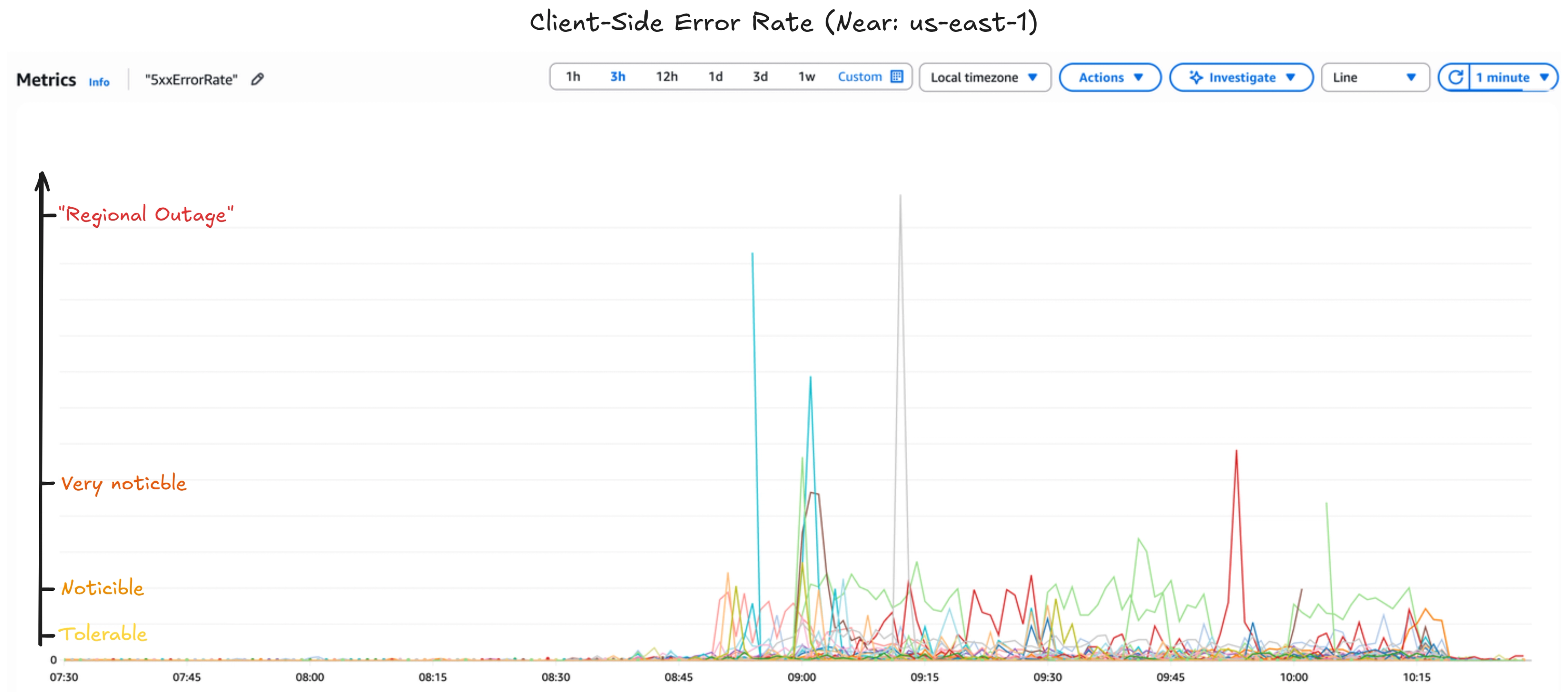

During the incident, we relied on a combination of Incident.io, DataDog, Sentry, and CloudWatch to tell us the story and communicate with potentially impacted customers. However, those services were at least partially impacted; the combination of multiple, plus manual effort, allowed us to investigate thoroughly. The following shows a CloudWatch graph highlighting the spikes in 5xx (errors) for customers located near us-east-1, mostly frontloaded, as well as gradual recovery towards the end of the incident (times are in UTC+1/BST/IST):

From the post-incident review, we had the following observations and fixes:

- The Docker image fetch bug was fixed almost immediately after the incident was closed.

- Our primary methods of communication (Zoom and Slack) had issues during the incident, and although we had fallbacks, we had some initial problems; we noted that we should add them to BC/DR processes.

- We required manual fallbacks for specific processes, such as deployment and incident management, due to the outage impact on other vendors we use; we noted the need to document these processes more effectively. The team was satisfied that we didn’t need any operational change with our vendors.

- The dependency on TrivyDB at runtime for scanning was identified as a potential failure point; we’ve taken action to automatically fail over to our own cache for this purpose (caching = less freshness). This failure was initially overlooked, so we’ve also taken action to enhance monitoring for this issue.

- Although we didn’t need to failover all clients near us-east-1 to another region (our closest region that services people is actually in us-east-2), we noted that it should be easier to route traffic away completely to reduce intermittent noise (e.g., via retries); we’re already working on Edge-based work related to this.

- Although the outage didn’t affect S3, and our confidence in it remains high, we did note a potential future impact for customers who store artifacts within specific regions for compliance reasons. However, we are developing new global storage topologies that remediate this issue. Watch this space.

So, we were not perfect, but it was good. The team did fantastic work with a highly unusual outage; as noted above, we required some manual fallbacks, and we had a reduced (or frustrated) ability to investigate, but the combination of our architecture and the strength of the vendors and platform we’re built on meant the storm was weathered. I’m confident that if us-east-1 had failed more extensively, it would have been problematic, but not catastrophic; although it is AWS’s control plane for some services, global routing would have continued.

I’m pleased to say that we had very few complaints during the outage, and despite it all, we still achieved our internal targets for overall availability. For those customers who were impacted, I know they felt that we were doing our best to minimize the disruption. Although operating a critical infrastructure service is high-stakes and high-pressure for the team, it’s also gratifying to be a crucial part of our customers’ operations. When they have problems, fixing (and preventing) them is hugely satisfying.

OK, that’s what happened at Cloudsmith; what about the 3Rs mentioned earlier?

Responsibility

Responsibility is simple. If you’re part of someone’s critical path as a dependency, then you own the results and outcomes. Not AWS. Not another vendor that you’re built upon. This truth doesn’t mean you can’t use vendors or trust them. No, it’s the complete opposite. It means you should, but like any other final link in the software supply chain, as the last touchpoint, the buck for accountability stops with you and your service. It’s a duty of care.

Winston Churchill once said that “the price of greatness is responsibility.” He wasn’t talking about distributed and high-availability systems, but the principle holds. Here, the greatness is the trust of your customers in your service, and the price is that you have to deliver on it, so you don’t get to point at someone else’s status page and say, “Not our fault.” You architect to prevent it. And you fix the problem, now or next.

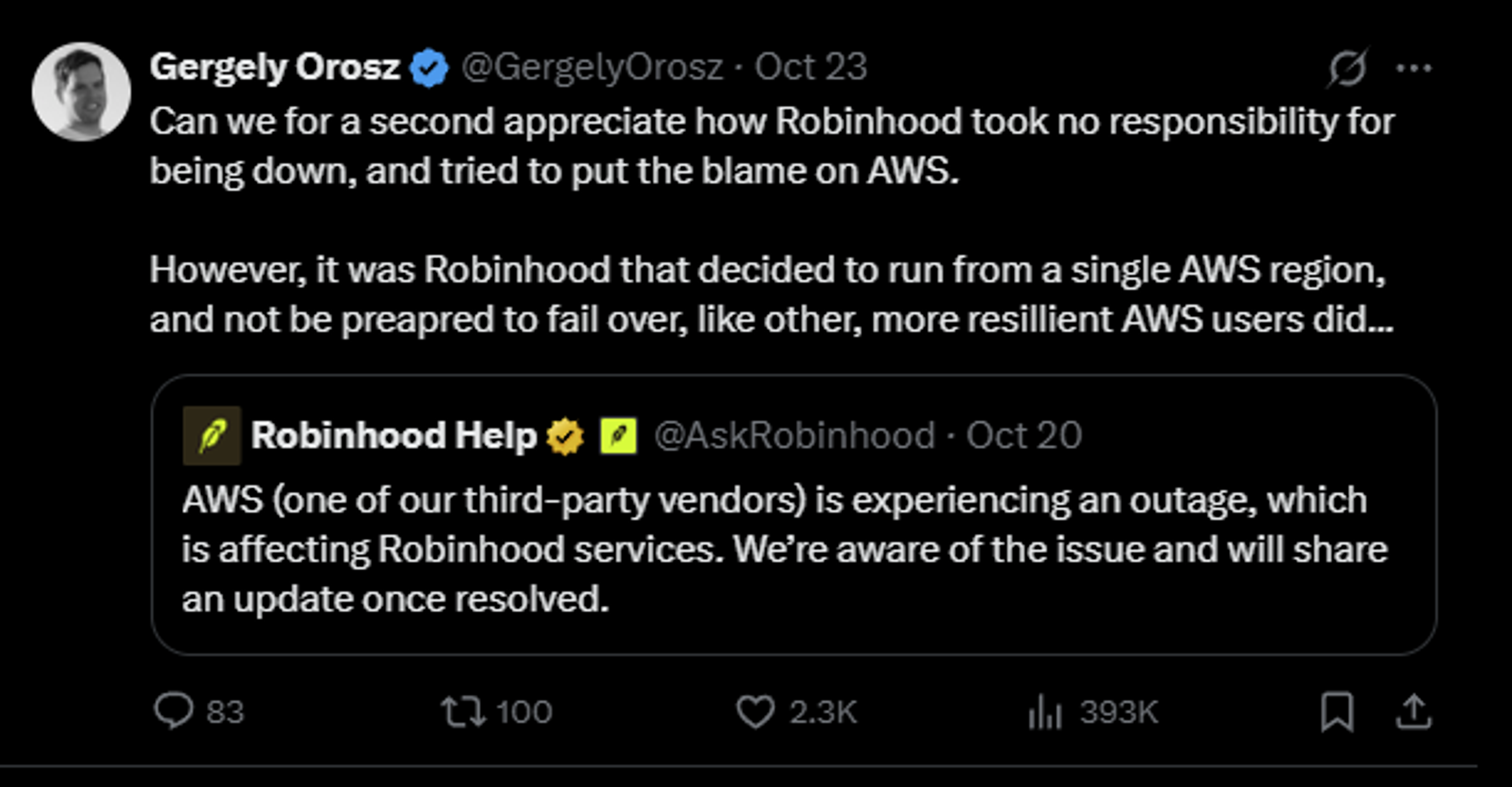

Although I’m loath to provide counter-examples of this, Gergely, who I mentioned earlier, tweeted that Robinhood, a popular market trading platform popular in the US, with a market cap of $125B, had issues throughout AWS’ outage in which people were unable to make or complete trades, because they hadn’t architected for multi-region. Their primary communication with users was “AWS is experiencing an outage”. It didn’t go down well (although I personally have no reason to think that Robinhood cares less about their users; they’ll be taking notes):

When a region goes down, customers don’t care which of your internal services or vendors broke, only that it broke them, indirectly or not. For a domain like Robinhood’s, it meant that the livelihood of people who rely on it for trading was completely locked out, personal or business, and perhaps critically so if they depended on the executed trades. By comparison, in our domain, our customers cared that they couldn’t fetch or deploy software on time. Completely different domains and use-cases, but the impact was equivalent; stopping you from working.

So for us, the responsibility for critical infrastructure means:

- We don’t blame vendors for our choices or the architectures we built.

- We stay accountable for the experience we deliver, even when it’s not a positive one.

- And when something breaks, we say what happened, what we did, and what we’re fixing.

It’s not a glamorous part of the job, but it’s probably the most important of the 3Rs, which leads us to the question of, if you’re highly responsible, what should you be doing as a service to ensure continuity?

Resilience

Resilience is the practical side of responsibility. If responsibility is the duty of care, then resilience is the method. If you’re building critical infrastructure, you don’t assume components behave or exist in an untouchable vacuum. You think they will fail. DNS breaks. Race conditions happen. Dependencies fall over. That one part of your logging pipeline that shouldn’t be critical but somehow disappears. Expect the unexpected.

And yeah, regions can fail. Cloud can fail. So, why AWS? I’m sometimes asked why we chose AWS and why we haven’t adopted a multi-cloud strategy yet. When we decided on AWS several years ago, there was no competition as to which Cloud was better; it was AWS, and I think it still is (but others are catching up). They’re a fantastic partner, enabling us to build a worldwide, fault-tolerant, resilient, highly available service.

I believe in the Shared Responsibility Model, which goes well beyond the context of security. Not only do we build for an ecosystem to work well with others, but we also believe in building on partnerships (more on that later). AWS, in particular, excels in both security and operational aspects of the Cloud. Cloudsmith focuses on security and operations in the Cloud. It’s a highly symbiotic match that allows us to do what we do at scale.

Multi-cloud is a whole other kettle of negative fish. We wouldn’t have the same symbiotic relationship, and trying to run our infrastructure in several drastically different ways would dilute our offering. It’d be OK for connectivity/routing; otherwise, I would be wary of saying multi-cloud is an excellent or good answer for resilience. It’s not. Cloud providers already provide tools to enable excellent, resilient architecture. Corey Quinn, of the Duckbill Group, wasn’t pulling too many punches when he said, “Multi-cloud is the worst practice.”

Boring > "Interesting" > Exciting. In other words, it just works, and works well.

Choose Boring Technology

Dan McKinley

Principal Architect, Etsy

So for us, the resilience for critical infrastructure means:

- Designing for failure from day zero, with a composable architecture built for redundancy and failover.

- Minimization of failure from dependencies and upstream services to reduce or isolate cascading failures.

- Expect the unexpected with escape hatches and (sometimes manual and unusual) fallbacks, for extreme scenarios.

If you think, “that sounds expensive”, you would be 100% right. Let’s just say that we had to justify the reason that our Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) was not particularly good early on. And yet, it’s the morally right investment if you’re building anything like we’re building. We did it, not because it was cool or shiny. Most people will never see it directly and will only feel its absence. No. It’s because resilience is the method to deliver on that duty of care.

OK, so it’s expensive to build and mandatory for critical infrastructure, but what’s the reality of running it?

Reality

You’ve probably guessed the reality already, but it’s still uncomfortable regardless of whether you’re a service provider or a service consumer. No matter what you do, how well you build it, or how much COGS you’ve turned into resilience, something will break in ways you didn’t expect, and people will be impacted. There are no magic bullets for this, and anyone claiming 100% uptime is probably telling porkies, or doesn’t have real users.

There is no perfect platform to build on that will protect you, but some do a better job than others. AWS, Google, Azure, Alibaba, DigitalOcean, a VPS provider, racks in your own data-center, your machine under the desk: all of them have outages, caused from any combination of mechanical gremlins and chaos monkeys, through to Human error and PEBCAK. Cloud platforms are not infallible gods. They’re software and people, at a massive scale.

OK, great, so we’re all doomed then? Well, no. Businesses are software and people, too. The whole world is just software and people. People know and understand that things break, but do you know what people like? Doing business with others who care, take their job very seriously, and exercise the appropriate care to build the thing well that others depend upon. Yes, the other 2Rs, responsibility and resilience.

They also appreciate partnerships, and good partners clearly communicate their expectations to each other. Corey said it pretty well in the above article, which applies more generally than the original quote, that “regardless of what provider you pick, once a [vendor is part of your critical infrastructure], they cease being your vendor and instead become your partner [...] Adversarial relationships aren’t nearly as productive as collaborative ones.”

A Tao of Cloudsmith we have is “Automate Everything,” but many people don’t know that the whole phrase for us was “Automate Everything, apart from the Human element.” So, this Tao means automating tedious tasks and allowing our customers more genuine Human contact. We had always intended for others to feel like we were just an extension of their org, an in-house team of experts in managing artifact management infrastructure for them.

So for us, the reality for critical infrastructure means:

- Everything will break eventually; it’s just a matter of space and time, so we must prepare for it.

- No perfect solutions will save you without effort; build for resilience responsibly.

- Be the best possible partner for those you serve; own it and communicate effectively.

If your customers walk away from an outage, no matter how bad it is, and they can say, “They were honest, they worked the problem, they kept us informed, they got us running, and they’re going to ensure it doesn’t happen again, if possible.” You did your job, and you’ve built a solid partnership. If they walk away unhappily saying, “They said AWS had an issue,” then you possibly didn’t. One evergreen quote that I love related to this is a classic from Charity Majors: “Nines don’t matter if users aren’t happy.”

Core Perspective

The 3Rs boil down to a simple philosophy that we tell ourselves:

- You play a crucial role in the supply chain.

- You don’t get to shout at your vendors.

- You don’t get to plead helplessness.

- You chose your architecture/design.

- You chose your resilience model.

- You own the entire blast radius.

- You own the uptime outcomes.

- You are critical infrastructure.

But when you take responsibility, build resilience, and accept the reality of your job, it’s beautiful.

There’s no better feeling than delivering the promises of good service. The primary objective is to implement those 3Rs with an architecture that aligns with an excellent product that others rely on. That’s what people pay for.

Cloudsmith exists because of the above. We’ve invested significant time and effort in building something truly resilient that others can depend on.

We’ll manage and maintain your software supply chain. That’s our job. You just ship.

More articles

By submitting this form, you agree to our privacy policy