Using vulnerability scoring systems to prioritize risks in your environment

Instead of wasting time clicking buttons in a UI, Cloudsmith gives dev teams the freedom to write their security rules as code for more power and flexibility. This approach, called policy-as-code, requires them to define precise limits/thresholds for what they consider a risky software artifact. When you're building policy-as-code, you can sometimes be stuck deciding exactly what thresholds to set for risky software artifacts. With a tsunami of vulnerabilities being thrown your way daily, it's impossible (and inefficient) to treat them all as emergencies. This blog post will help you understand the various scoring systems you can use to build smarter, context-aware security policies.

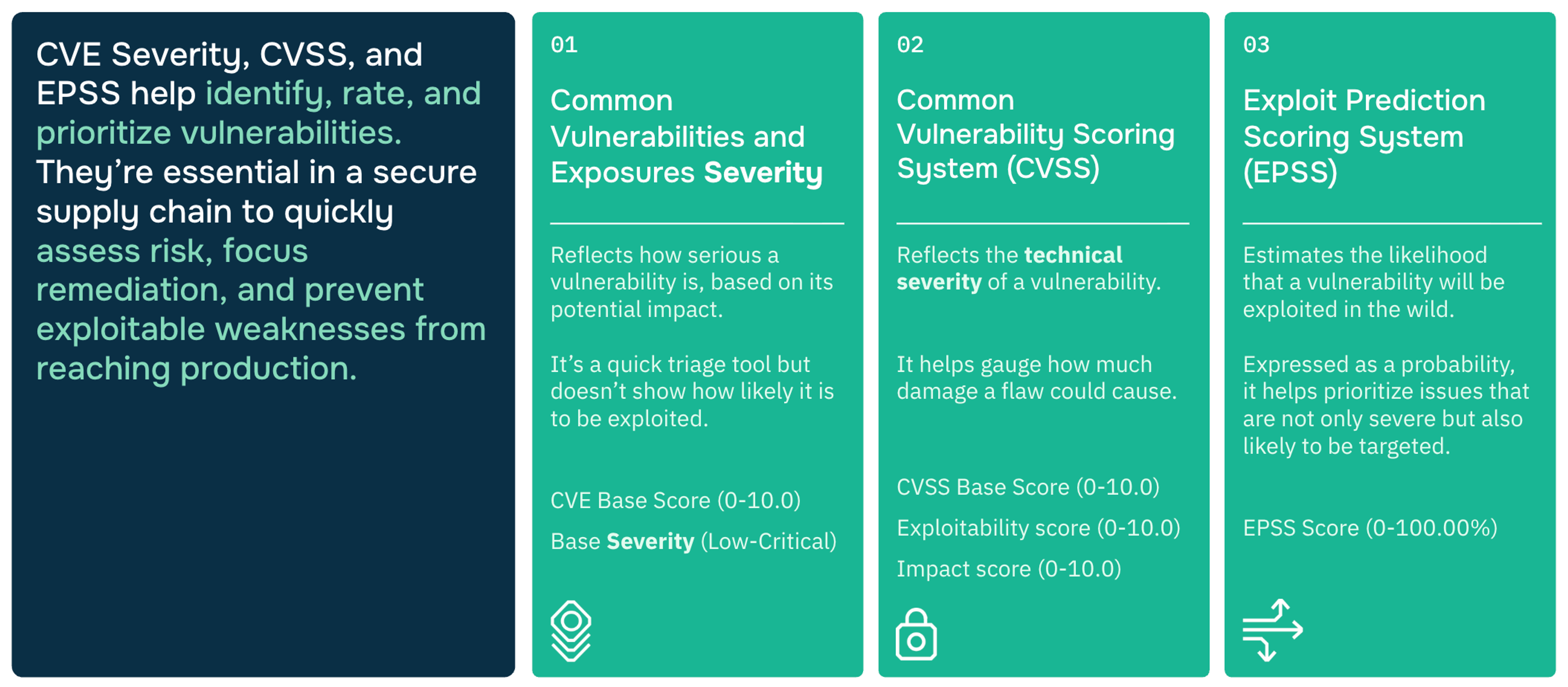

What is CVSS (Common Vulnerability Scoring System)?

For years, the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) has been the industry standard for rating the severity of vulnerabilities. It provides a numerical score from 0.0 (Low) to 10.0 (Critical), giving security teams a consistent way to assess risk.

A CVSS score is derived from three metric groups:

- Base Score: Assesses the intrinsic qualities of a vulnerability, like the attack vector, complexity, and impact on confidentiality, integrity, and availability. This is a theoretical, worst-case assessment.

- Temporal Score: Reflects characteristics that change over time, such as the availability of exploit code or an official patch.

- Environmental Score: Allows you to customize the score based on your specific environment, considering factors like the importance of the affected system.

While CVSS is excellent for understanding a vulnerability's theoretical potential for harm, it can't answer the most important question: "Does this actually pose a threat to my environment right now?"

Why Do Some CVEs Lack a CVSS Score?

You'll often find a CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) identifier without an accompanying CVSS score. This happens for a few reasons:

- Timing: A CVE ID is often assigned the moment a vulnerability is disclosed. The detailed analysis required to calculate a CVSS score comes later from non-profit organisations like the NVD (National Vulnerability Database).

- Scope: Some vulnerabilities affecting obscure products or deemed too minor may never get formally scored.

- Disputes: If researchers and vendors disagree on a vulnerability's impact, it might remain un-scored until a consensus is reached.

What is EPSS? (Exploit Prediction Scoring System) and Why It Matters for Risk Prioritization

This is where the Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS) changes the game. Managed by FIRST.org, EPSS doesn't measure theoretical severity; it estimates the probability (from 0% to 100%) that a vulnerability will be exploited in the wild within the next 30 days.

A high CVSS score signals potential danger, but EPSS provides the real-world context needed to answer critical questions like:

- "Is anyone actually exploiting this?"

- "Is this vulnerability reachable from the internet?"

- "Does it impact a critical system?"

EPSS uses a machine learning model trained on vast datasets of vulnerability and threat intelligence. It's continuously updated to provide daily probability scores, helping you focus on the threats that are most likely to materialise.

It’s important to note that the EPSS model itself is updated periodically to maintain its predictive accuracy. For example, EPSS v4 was introduced on March 17, 2025, to improve performance.

EPSS Score vs. EPSS Percentile

When you look up an EPSS value, you'll see two numbers:

- EPSS Score: The direct output of the model. This is the probability of exploitation. (for example 0.92, or 92%).

- EPSS Percentile: Ranks a vulnerability against all others. A percentile of 0.98 (or 98%) means this vulnerability is more likely to be exploited than 98% of all other CVEs.

CVSS vs. EPSS: A Quick Comparison

| Aspect | CVSS | EPSS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Measures vulnerability severity | Predicts exploitation probability |

| Score Range | 0.0 to 10.0 | 0 to 1 (probability) |

| Update Frequency | Static (Unless manually updated) | Daily |

| Methodology | Expert-driven framework | Data-driven Machine Learning |

| Complexity | Complex (3 metric groups, multiple sub-scores) | Simple (Single Probability Score) |

| Context Consideration | Through environmental metrics | Through real-world exploitation data |

| Industry Maturity | Well-established (20+ years) | Emerging standard |

| Primary Use Case | Vulnerability severity assessment | Exploitation risk prioritisation |

| Data Source | Theoretical assessment | Real-world exploitation data |

| Adapatability | Manual updates needed | Automatically adapts to new threats |

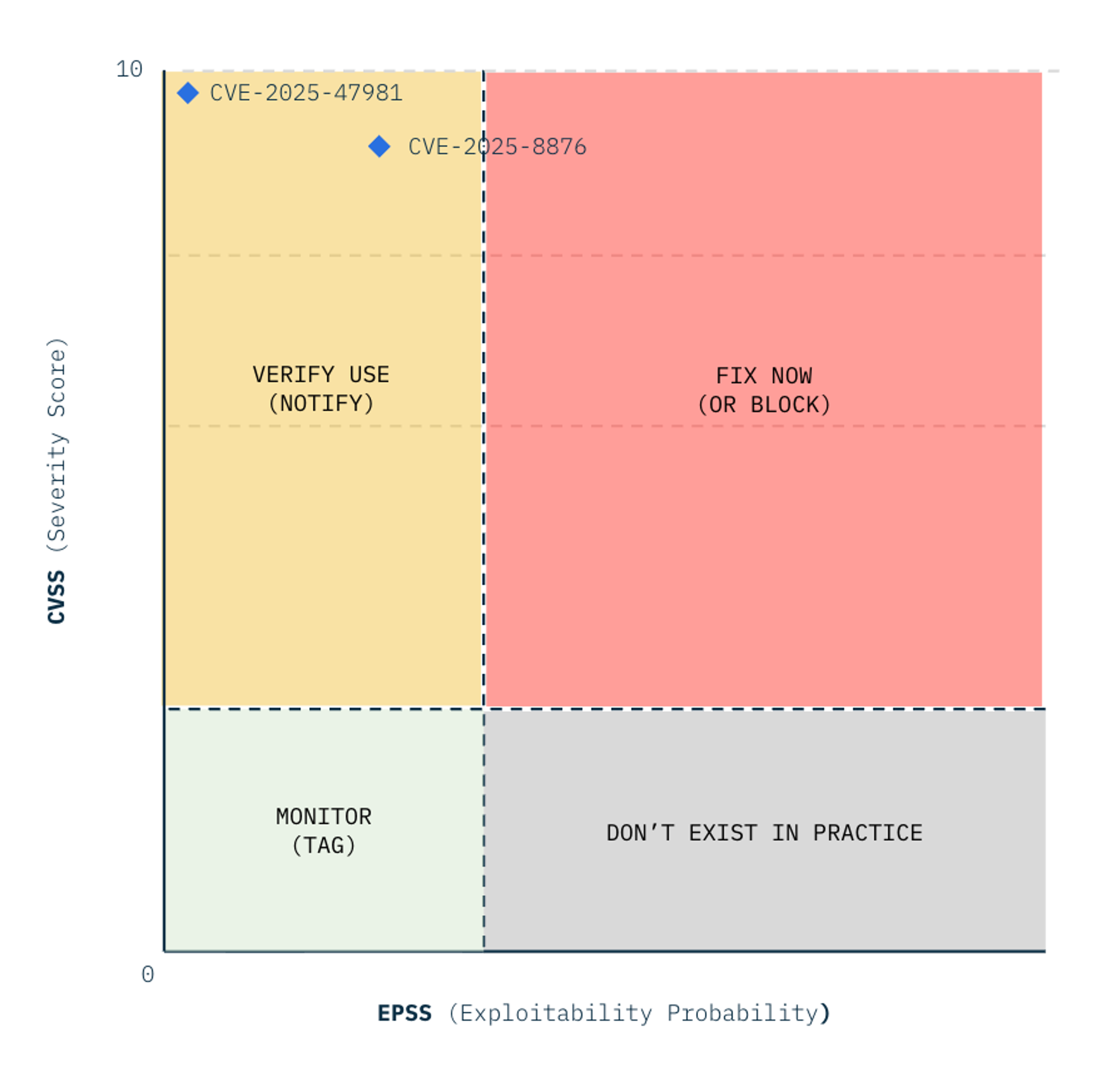

How to Build a Risk-Based Vulnerability Triage Strategy Using CVSS, EPSS, and KEV?

Neither CVSS nor EPSS tells the whole story alone. The most effective strategy combines them with other key data points, like the CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog, which lists vulnerabilities that are actively being exploited in real-world attacks.

By layering these sources, you can move from a theoretical risk assessment to an evidence-based one. Imagine you have thousands of vulnerabilities. Instead of chasing every "Critical" CVSS score, you can narrow your focus dramatically.

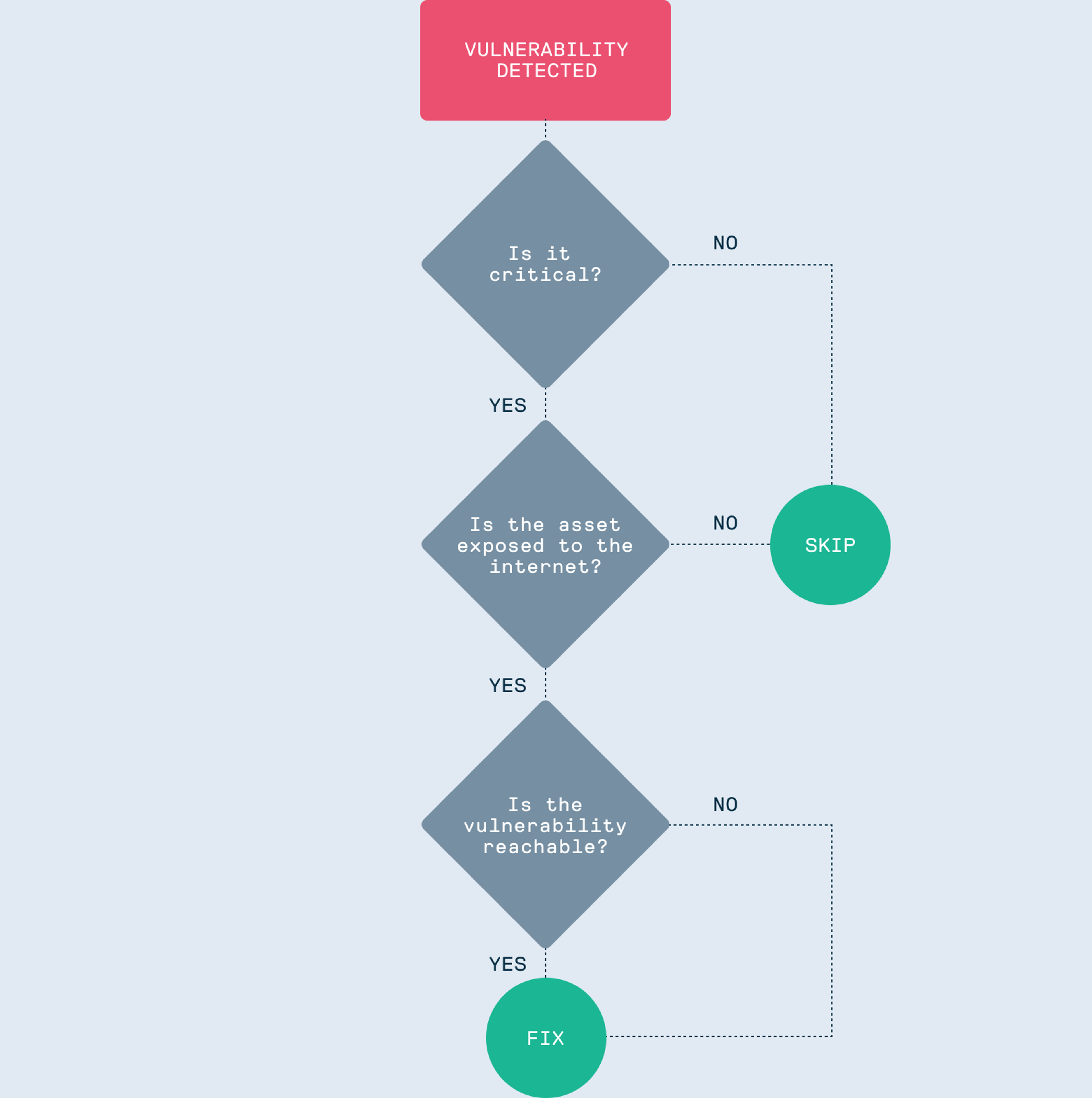

The goal is to get to a workflow like the one depicted above. Of 922 known vulnerabilities, 352 might be rated "Critical" by CVSS. But by applying EPSS, you might find that only a small fraction have a high probability of exploitation. Add in context, like whether the package is actually in use and has a fix available, and you can pinpoint the few vulnerabilities that demand immediate attention.

The Vulnerability Triage Matrix

Here is a practical matrix you can adapt for your own security policies to decide when it's okay to use a package versus when you need to take immediate action.

- Use the matrix to prioritize fixes by combining severity, exploitability, and context in CVE details.

- Don’t rely on labels alone.

For example, a “High” CVE with low CVSS and EPSS may not need urgent action. - Always assess whether the vulnerability is actually exploitable in your environment. Do this before deciding to block or patch a vulnerable software package.

| CVE Severity | CVSS Score | EPSS Score | Interpretation | Action | When it’s OK to use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOW | 0.1-3.9 | <10% | Low impact, unlikely to be exploited | Monitor only | Safe to use unless in regulated environments |

| MEDIUM | 4.0-6.9 | <10% | Moderate impact, low exploitability | Patch in next update cycle | OK to use if non-critical package |

| HIGH | ≤6.9 | <5% | Mismatched severity and score – possibly inflated label | Verify CVE details; use with caution | OK if exploit is theoretical or not applicable in your setup |

| HIGH | 7.0-8.9 | >30% | Serious issue with real-world exploit potential | Prioritise patching or mitigation | Use only if there’s no exposed vector in your deployment |

| CRITICAL | 9.0-10.0 | >50% | High-impact and high-likelihood of exploit | Patch immediately or block usage | Rarely OK to use — isolate or sandbox if unavoidable |

| CRITICAL | 9.0-10.0 | <50% | Dangerous in theory but unlikely to be exploited | Assess if attack vector applies | Use in internal-only or air-gapped environments |

High CVSS but low EPSS

Both were assessed “High” by CVSS due to potential impact/scope if triggered, but EPSS (being telemetry/data-driven) remained very low because there was little to no evidence of widespread attacker uptake.

| CVE | What is it | CVSS v3.x | EPSS (prob. next 30 days) | Why EPSS stayed low |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2024-0646 (Linux kernel KTLS out-of-bounds write) | Local crash / potential LPE via KTLS splice path | 7.0 (High) | 0.04% | Local preconditions + specialized path → little opportunistic exploitation observed in the wild. |

| CVE-2024-25062 (libxml2 UAF in XML Reader + XInclude) | Network-reachable DoS conditions in specific parser modes | 7.5 (High) | 0.05% | Needs crafted XML + specific feature toggles; few mass-exploitation signals. |

CVE-2024-0646 in the Linux kernel had a CVSS of 7.0 (High) but an EPSS of just 0.04%. Why? Its exploitation requires local access and specialised conditions, making it an unattractive target for widespread attacks.

High EPSS before NVD had published details

CVE-2024-4577 (a critical PHP vulnerability) had an EPSS score of ~94% days before the NVD published its full analysis and CVSS score. Teams relying only on NVD/CVSS feeds would have been blind to a major, actively exploited threat.

| CVE | EPSS Score | CVSS v3.x | CVSS Reg. Date | NVD “Published Date” |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2024-4577 (PHP-CGI argument-injection, RCE) | ~0.94 (94%) | 2024-06-09 | Public research & exploit chatter spiked quickly; Cytidel notes it was “on our radar for ~3 days before NVD publication,” so any scans in that window would miss NVD while EPSS already signaled high exploit potential. | |

| CVE-2024-1709 (ConnectWise ScreenConnect auth bypass → RCE) | ~0.94 (99th percentile) | 2024-02-21 | Disclosed 2024-02-19; widely exploited and quickly weaponised. If artifacts were scanned on 02-19 or 02-20, NVD wasn’t published yet, but EPSS (and threat intel) already indicated extreme risk. |

Why Traditional Vulnerability Management Fails in DevSecOps Pipelines

- Don’t let CVSS alone drive queues.

Blend EPSS (likelihood), KEV (known exploitation), and exposure context (is it reachable/authenticated?). For example, treat CVE-2024-4577 and CVE-2024-1709 as urgent even if your NVD-only feeds lag. - Watch for publication gaps.

When the NVD record date is later than public disclosure/research, lean on EPSS + vendor advisories + KEV until NVD catches up.

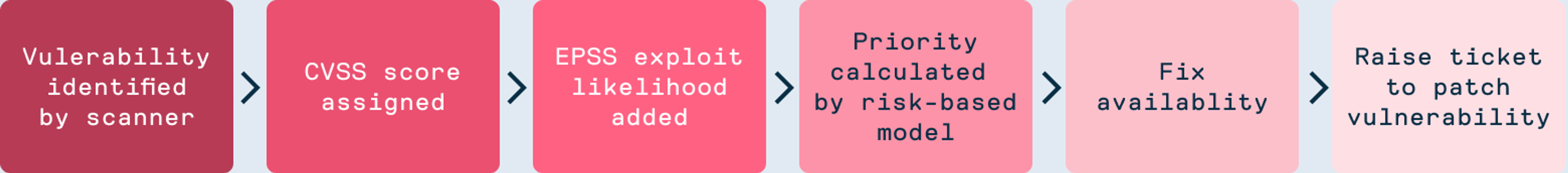

While it’s one thing to enumerate vulnerabilities within a platform, it’s another thing to enable our customers to manage the vulnerabilities in an effective way to reduce organisational risk as quickly as possible, while not impeding on development processes.

Traditional Inefficient Workflow:

- Security tool identifies a vulnerability

- Creates a generic ticket: “CVE-2024-XXXX found in package Y”

- Developer stops current work to research CVE while vulnerable package remains deployed in staging or production

- Developer figures out which version fixes the vulnerability

- Developer tests compatibility

- Developer deploys fix

- Result is days/weeks per vulnerability

Beyond EPSS: Combining Scoring Systems for Smarter Vulnerability Management

While EPSS is valuable in implementing a risk-based vulnerability management approach, it has limitations that have to be considered when integrating EPSS within a broader security strategy. For one, EPSS scores are only applicable to vulnerabilities with CVE identifiers, so unknown or unreported vulnerabilities (including zero-day vulnerabilities) that haven’t been cataloged with a CVE identifier are not covered.

EPSS should be part of a larger strategy, as organisations benefit more when they use EPSS along with CVSS and other vulnerability prioritization methods. The CISA KEV (Known Exploits) catalog, for example, informs security professionals if the vulnerability has already been successfully exploited in the wild. Combining EPSS, CVSS, and CISA KEV allows organisations to implement risk-based more effective vulnerability management.

A Modern, Risk-Based Workflow

Modern vulnerability management isn’t just about finding what's broken; it's about knowing if it actually matters. By combining CVSS, EPSS, and CISA KEV, you can build an automated triage system that only flags what's truly urgent.

This smarter lifecycle asks four simple questions:

- Is this a severe vulnerability (CVSS)?

- Is it being actively exploited or likely to be (EPSS, CISA KEV)?

- Is the affected asset internet-facing or part of a critical system?

- Is there a fix available?

If the answer to all is "yes," you act. If not, you can de-prioritize it and let your developers focus on what they do best: building great software.

Toward a smarter vulnerability lifecycle with Policy-as-Code

This triage model reflects the realities of limited time, team resources, and the explosion of third-party software risk. Users are advised to focus primarily on CVEs associated with in-use packages that have a known fix available. If there’s no fix available, we cannot take proactive steps to patch the known vulnerable packages.

Likewise, if the software package is not in-use or does not have access to the public internet, oftentimes the exploitability is near zero. In this workflow, an organisation or security team that has roughly 117,000 CVEs in their software supply chain equates to something like 144 in-use vulnerable workloads that actually require urgent attention from development teams.

Additional Learning Material

- Webinar: Enforcing Artifact Management Policies in OPA

- eBook: Cloudsmith's Rego Policy Cookbook

- Blog: Compliance policies in Cloudsmith EPM

More articles

Eliminating ambiguity: The case for explicit Docker image paths